Caring is human – and animal. Mice, monkeys, and ants also care for one another to an astonishing degree. Now, even attempts at resuscitation have been observed.

In emergency situations, we have standardized first aid measures at our disposal. These include, if necessary, life-saving measures such as cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) . Mice also come to the aid of their fellow mice when they are injured or unconscious—a behavior that was previously attributed primarily to humans. Scientists at the Keck School of Medicine at the University of Southern California (USC) have discovered in a study that the rodents perform a kind of mini-resuscitation.

Cleaning and biting

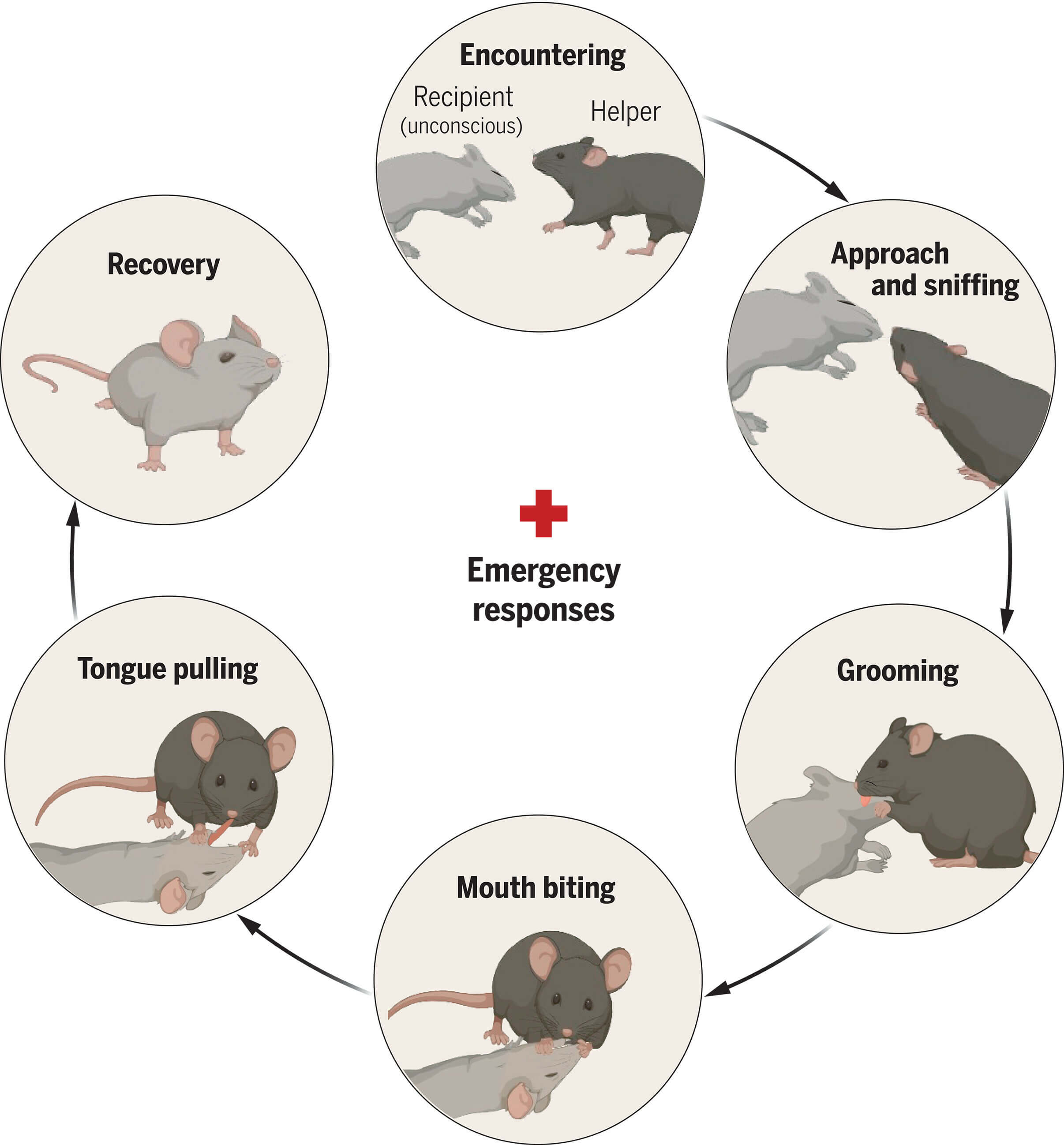

The mice actively respond to unconscious conspecifics. Their behavior ranges from cautious sniffing and grooming to more intense measures such as gently biting the affected animal’s snout or tongue. In some cases, the mice even attempted to pull out their conspecific’s tongue—possibly to clear the airways and accelerate recovery. Their behavior may be deeply rooted in evolution.

Mice also provide first aid. Credit: Sun et al.

Mice also provide first aid. Credit: Sun et al.

What was particularly striking was that these reactions occurred more frequently between familiar pairs of mice and were almost never observed when one mouse was just sleeping or dozing.

Scientists made the discovery serendipitously during other animal studies. Wenjian Sun, lead author of the study and a researcher at the Keck School of Medicine, emphasizes that such behavior has never been documented in mice before. The similarities to human first aid are striking and raise new questions about social care in the animal kingdom.

A look at neurobiology

To investigate the neurological basis of this remarkable behavior, the research team used neural imaging and optogenetics. They found that the helper mice’s behavior was associated with increased activation of oxytocin neuropeptides.

Oxytocin is a hormone that plays a central role in social bonds. In humans, it is associated with feelings such as trust, attachment, and affection. According to a study, oxytocin also plays a central role in altruistic helping in mice.

The scientists are now planning further studies to determine whether mice exhibit even more complex reactions to unconscious conspecifics. They want to investigate whether these behaviors are purely instinctive or whether they indicate a deeper social understanding. These findings could provide new insights into animal social interactions and possibly even parallels to human behavior. But astonishing behaviors don’t only occur in mice.

Monkeys treat fellow monkeys – or themselves

Chimpanzees use certain plants for self-medication to combat parasitic infestations. For example, they swallow the furry, slightly spiny leaves of the plant Aspilia mossambicensis whole. These leaves pass through the digestive tract virtually intact and help excrete intestinal parasites, as worms cling to the hairy surface of the leaves.

Scientists have also observed that chimpanzees deliberately apply insects to their own wounds and those of other chimpanzees to speed up healing. Now, plans are underway to collect and analyze the insects used to study their potential anti-inflammatory or pain-relieving properties in detail.

Ants bring injured individuals back to the nest

Further examples come from the insect kingdom: The African ant Megaponera analis has developed an extraordinary strategy to minimize its losses in the fight against termites. As a specialized hunter, it exposes itself to considerable risks to capture termites. But the ants exhibit surprising rescue behavior.

After a fight, healthy ants carry their injured ants back to the nest. These ants have often lost limbs. They can recover in the protection of the nest. Experiments have shown that two chemical compounds—dimethyl disulfide and dimethyl trisulfide—trigger this rescue behavior. Both chemicals have been studied, among other things, as odorous compounds in fungi.

Not only the individual benefits from rescue behavior. Mathematical models show that colonies grow by almost a third. The study provides experimental evidence of evolutionary advantages when ants rescue their conspecifics.

| Sources:Sun et al.: Reviving-like prosocial behavior in response to unconscious or dead conspecifics in rodents. Science, 2025. doi: 10.1126/science.adq2677Frank et al.: Saving the injured: Rescue behavior in the termite-hunting ant Megaponera analis. Sci Adv , 2017. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1602187Mascaro et al.: Application of insects to wounds of themselves and others by chimpanzees in the wild. Curr Biol , 2022. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2021.12.045 Image source: created with DALL-E |

Article by, Docchek.